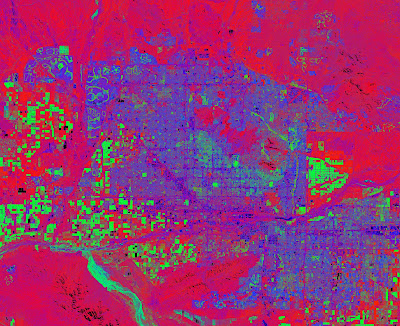

Where you live may say a lot about your socioeconomic status. It also may suggest how vulnerable you are to long periods of excessively hot weather. Researchers at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, Arizona State University and the University of California at Riverside are studying the relationship between temperature variations and socioeconomic variables across metropolitan Phoenix. They have found that the urban poor are the most vulnerable to extreme heat.Those in higher incomes tend to live in areas that are cooler due to the increased amount of vegetation, such as lush lawns and canopy trees, that surrounds homes or on higher-elevation hillslopes above the hotter Salt River valley floor.

The urban poor tend to live in the urban core of metro Phoenix where the heat island effect is intense. These neighborhoods are located near industrial areas, commercial centers, and transportation corridors. There are few amenities, such as parks, and the landscaping has little or no grass or trees. Propelled by a $1.4 million grant from the National Science Foundation as part of its Dynamics of Coupled Natural and Human Systems Program, the research team is compiling a history of the development of the metro Phoenix urban heat island. Urban heat islands result when existing soil and grass is replaced with materials such as asphalt and concrete that absorb heat during the day and reradiate it at night, thus causing increased temperatures especially during nighttime.

Sharon Harlan, a sociologist in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change at ASU, has pulled together the interdisciplinary team, which is comprised of social and natural scientists, public health experts, and educators. Harlan is excited about the potential for this pioneering research. “The problem of heat related deaths and illnesses is very serious,” said Harlan. “Each year, heat fatalities in the U.S. occur in greater numbers than mortality from any other type of weather disaster. Global climate changes and rapidly growing cities are likely to compound and intensify the adverse health effects of heat islands around the world. Our research is integrating data with sophisticated modeling tools to analyze urban systems while keeping health equity considerations and the well-being of vulnerable populations at the center of attention. We want our research to be used to promote better decision-making about climate adaptation in cities.”

The urban poor tend to live in the urban core of metro Phoenix where the heat island effect is intense. These neighborhoods are located near industrial areas, commercial centers, and transportation corridors. There are few amenities, such as parks, and the landscaping has little or no grass or trees. Propelled by a $1.4 million grant from the National Science Foundation as part of its Dynamics of Coupled Natural and Human Systems Program, the research team is compiling a history of the development of the metro Phoenix urban heat island. Urban heat islands result when existing soil and grass is replaced with materials such as asphalt and concrete that absorb heat during the day and reradiate it at night, thus causing increased temperatures especially during nighttime.

Sharon Harlan, a sociologist in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change at ASU, has pulled together the interdisciplinary team, which is comprised of social and natural scientists, public health experts, and educators. Harlan is excited about the potential for this pioneering research. “The problem of heat related deaths and illnesses is very serious,” said Harlan. “Each year, heat fatalities in the U.S. occur in greater numbers than mortality from any other type of weather disaster. Global climate changes and rapidly growing cities are likely to compound and intensify the adverse health effects of heat islands around the world. Our research is integrating data with sophisticated modeling tools to analyze urban systems while keeping health equity considerations and the well-being of vulnerable populations at the center of attention. We want our research to be used to promote better decision-making about climate adaptation in cities.”

No comments:

Post a Comment